Morbidity associated with the donor site after harvesting free fibula flaps is generally considered low and most commonly related to complications associated with the healing of split skin graft closures. The occurrence of donor site ischemia following the harvesting of a fibula flap is uncommon, but if the event occurs, it may have catastrophic consequences. In this paper, the authors present a case study describing an ischemic lower limb following a free fibula harvest for head and neck reconstruction. A postoperative angiography revealed occlusion of the remaining anterior tibial and posterior tibial vessels, with only collateral circulation supplying the lower leg. In order to restore circulation to the leg, endovascular angioplasty of the anterior tibial artery was performed. Upon healing of the free osseocutaneous fibula flap at the recipient site (without complications), the patient was discharged and scheduled for outpatient follow-up. As a result of unfavorable wound healing at the donor site despite endovascular interventions, the patient's lower limb was later amputated below the knee. The authors present an overview of the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative strategies for diagnosing and managing complications associated with free fibula flap harvests.

Osseous free flaps are considered the gold standard for the reconstruction of larger osseous defects due to head and neck cancer, as its success rate is over 95% in most centers [1,2]. Free osseocutaneous fibula flap, described by Wei et al. [3] and later popularized by Hidalgo [4], is often referred to as the most commonly used flap to reconstruct the mandible. Among its benefits are a long pedicle with wide diameter vessels, a long bone suitable for osteotomies, and an ability to be harvested simultaneously with tumor removal [5,6]. There are also other osseous flaps that are less frequently used for a variety of reasons: the osseous radial forearm flap was long ago abandoned due to the risk of fractures and sensory disturbances; the iliac crest flap has an ideal bony stock, but has a substantial skin paddle, which makes it unsuitable for intraoral lining and increases the risk of herniation; and typically the scapula flap requires intraoperative repositioning of the patient and is difficult to harvest simultaneously with tumor removal [7-12]. The use of the scapula in osseous head and neck reconstruction is slowly gaining momentum. However, it has yet to take over from the free fibula flap, which still dominates this procedure.

Free fibula flaps have earned a stellar reputation; however, they do not always disclose significant donor site complications that may complicate the surgery. Various studies have revealed that chronic ankle pain and mobility issues can be unpredictable and potentially debilitating [13-16]. In contrast, compartment syndrome and vascular ischemia are not often mentioned in the literature, but their occurrence is possibly preventable. By predicting and preventing donor site complications, free flap surgery can more readily measure success based on donor site morbidity. The presented case illustrates the unfortunate consequences of lower limb ischemia resulting from vascular stenosis following a free fibula flap harvest. Furthermore, the authors discuss preoperative, postoperative, and intraoperative strategies for identifying and managing at-risk limbs.

We describe here the case of a patient who developed critical ischemia in the lower extremity following free fibula flap reconstruction of the mandible at Uppsala University Hospital in Sweden. A written consent was obtained for the use of the patient's images for publication, and data was handled according to our institution's research ethics policies (ethical approval number DNR 2017/207).

The patient was an 84-year-old woman who had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, arrhythmias, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. She presented with pT4aN0M0 gingival squamous cell carcinoma involving the right hemi-mandible. A multidisciplinary tumor board recommended resection of the hemi-mandible, a unilateral neck dissection, and a free fibula flap reconstruction. In the preoperative clinical assessment of the lower leg, no palpable pulses were found. A handheld doppler however, demonstrated adequate flow in the dorsalis pedis artery. Due to the high blood creatinine levels, a computerized tomographic angiography was not recommended.

After the successful completion of the surgery, a mandibular reconstruction was performed with the right fibula, and the donor site was closed with a split skin graft. The ischemia time during the surgery was less than 90 minutes. In accordance with the established protocol for our department, the patient was given low-molecular-weight-heparin as a prophylactic dose prior to surgery and acetylsalicylic acid and low-molecular-weight-heparin as a follow-up dose following surgery.

The right foot showed reduced circulation on day one following surgery along with diminished capillary refill. The patient subsequently developed necrosis of the medial aspect of the forefoot with additional necrotic patches developing over the foot and lower leg. In an urgent postoperative angiography, it was found that the remaining anterior tibial and posterior tibial vessels had been occluded, leaving only collateral circulation supplying the lower leg (Figure 1A). After consulting with the vascular surgery department, an attempt was made to restore circulation of the leg by performing an endovascular angioplasty of the anterior tibial artery. As the Doppler signal in the tibialis anterior was restored after the procedure, no additional intervention was needed.

Figure 1. (A) An angiography of the lower leg postoperatively shows collateral circulation and occlusion of the remaining anterior and posterior tibial vessels. (B) A clinical observation at the donor site postoperatively indicates necrosis of the first and second toes, as well as the dorsum of the foot. (C) A postoperative photograph demonstrates necrotic muscles in the lateral compartment.

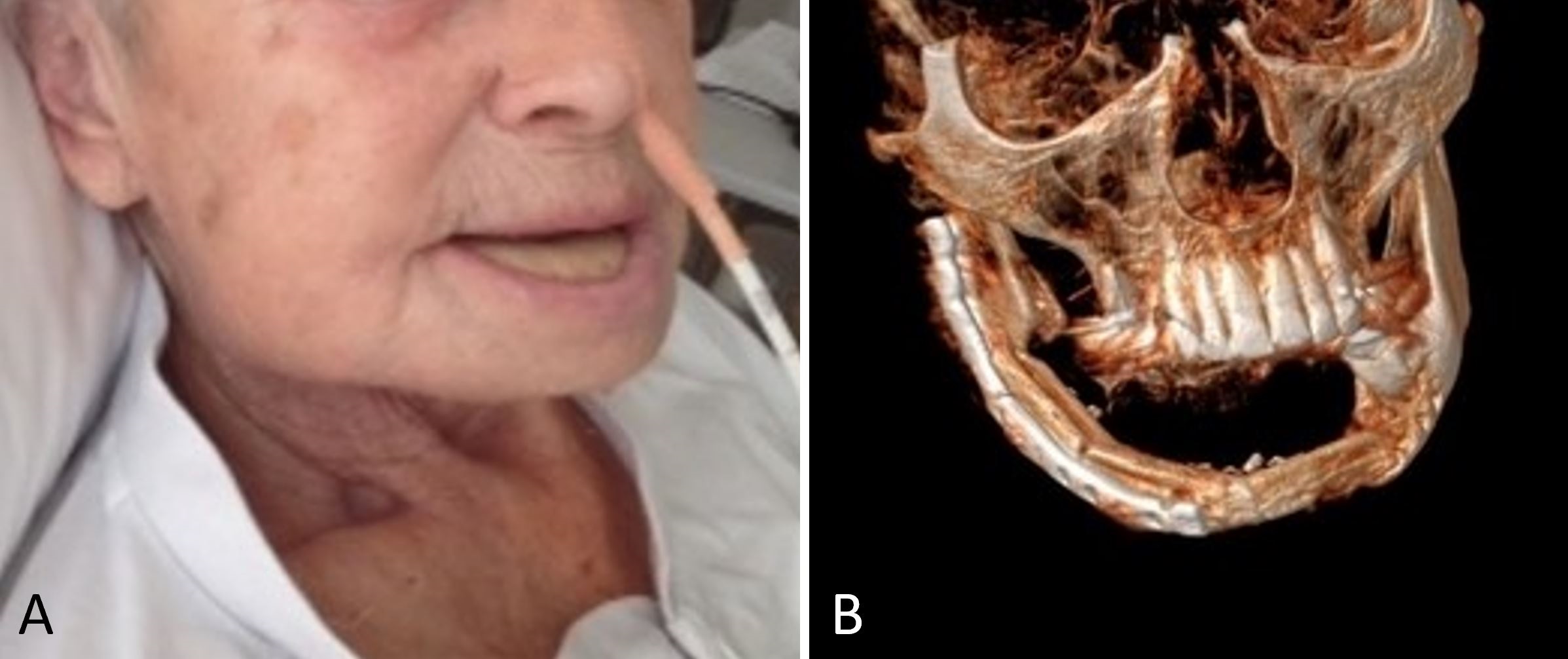

Following serial debridement, it was discovered that the patient had necrotic muscles in the lateral compartment, which were also debrided along with the necrotized great toe (Figure 1B-C). With the use of negative pressure wound therapy and skin grafting, the resulting defects were covered. Furthermore, during the patient's hospital stay, the patient suffered from chest pains, for which a diagnosis of myocardial infarction was made, which was treated medically. In the end, the free osseocutaneous fibula flap healed into the recipient site without complications (Figure 2), and the patient was discharged and scheduled for follow-up in the outpatient clinic. Following the initial surgery, the patient experienced an unfavorable healing response in the lower limb and was therefore required to undergo a below knee amputation of the affected leg.

Figure 2. (A) A postoperative photograph demonstrating satisfactory wound healing without complications at the recipient site. (B) The free osseocutaneous fibula flap heals into the recipient site and provides the recipient with the full shape of the mandible.

Complications related to the donor site following free fibula flap harvests are frequently attributed to delayed wound healing during the early phase of the postoperative course. However, chronic pain and/or gait disturbances have been reported as a result of donor site complications in the long-term [13-16]. The risk of serious complications following an ischemic event is rare [7,8,17,18]. However, vascular anomalies, peripheral vascular disease (particularly in the elderly population), and tight closure of the donor site are known factors which can lead to ischemia in the lower leg following a fibula flap harvest [19-22]. In the following discussion, we analyze their occurrence and suggest strategies for identifying and managing them (Table 1).

Management of Vascular Anomalies

There have been several vascular variations and dominance patterns described for the lower limb, which may limit the harvesting of the fibula flap. Kim et al. reported three main types of infra-popliteal arterial variations (types I-III) based on varying branching patterns [23]. For a free fibula flap harvest, the most critical subgroup is type IIIC, which represents the dominant peroneal artery as the only contributing artery to the foot. As a result of hypoplastic and/or aplastic anterior and/or posterior tibial arteries, the peroneal artery becomes the only artery to supply blood to the foot, a condition known as peronea arteria magna, whose prevalence has been reported to range from 0.2% to 8.3% [24-27]. Based on a systematic review of 5790 limbs from 26 studies, Abou-Foul and Borumandi found that critical infra-popliteal vascular anomalies are present in 10% of the population, with a predominance of the peroneal artery in 5.2% [26]. The same group reviewed 18 articles with 26 cases of free fibula harvests in patients with known peroneal artery dominant lower limbs in a subsequent article [24]. It was found that five cases (one of which was a true type IIIC peronea arteria magna variant) had undergone successful harvests after intraoperative clamping had revealed adequate distal perfusion, as well as two cases that were not radiologically evaluated prior to surgery and did not display intraoperative suspicion of peronea arteria magna. Following surgery, these two patients both developed severe ischemia and needed interposition vein grafts to re-establish blood flow. Another rare vascular variant on the lower limb is the low division of the tibio-peroneal trunk [28], which might require the sacrifice of the posterior tibial artery as well as the placement of a vein graft to bridge its gap.

Even though the peronea arteria magna is described as a relative rather than an absolute contraindication for fibula flap harvest, it would be helpful to be aware of its presence before the surgery in order to make an informed surgical decision [29]. When an unexpected intraoperative finding is determined to be associated with a peronea arteria magna, it can be attempted to diagnose the condition by clamping the peroneal artery at the distal portion of the fibula in order to determine if perfusion is available to the foot. When there is a suspicion of ischemia, an oximeter can be placed on the great toe to assess the blood flow. If diminished perfusion is evident, the surgeon should abandon the flap or use a long vein graft to bridge the peroneal artery gap if it is to be used. The presence of a low tibio-peroneal division would also necessitate the use of a vein graft to bridge the resulting gap in the posterior tibial artery. Although one could consider harvesting the fibula as a non-vascularized bone graft, grafting larger than 5 cm is not recommended [30].

Management of Vascular Stenosis

Atherosclerosis-induced vascular stenosis can have devastating effects on the flap and the donor site. Old age and/or diabetes are risk factors for atherosclerosis, which should alert the surgeon to possible complications [31].

There should be a combination of examinations performed prior to surgery. Palpable pulses can lead to confusion, as retrograde arterial flow is capable of causing palpable pulses as well as concealing proximal stenosis. Allen's test may be useful in determining the degree of proximal perfusion to the foot from non-compressed vessels. Handheld dopplers are often used, but until the user is familiar with the meaning of the waveform and the functions they perform, they may present similar problems to manual palpation. Waveforms can be characterized as triphasic, biphasic, or monophasic, with monophasic waveforms indicating significant stenosis [33]. In the lower limb, the ankle-brachial-pressure index is commonly used to determine if a patient has atherosclerosis, but the results can be inaccurate due to the incompressibility of stiff vessels. It is preferred to measure great toe pressure rather than ankle pressure since the great toe digital vessels are less prone to atherosclerosis. During a preoperative vascular clinical evaluation, it is imperative to recognize that the clinical examination may lead to an unjustified sense of security when it comes to interpreting the vascular supply to the lower extremity. Even normal palpable pulses and audible Doppler signaling cannot guarantee the presence of a sufficient blood supply.

To prevent misinterpretation, a radiologic examination of the perfusion and/or flow pressure is imperative. A computed tomography angiography is often performed, however magnetic resonance imaging or color duplex ultrasound are more appropriate for patients with poor renal function [34]. Alternatively, intravenous fluid infusions can be applied before and after the computer tomographic angiography to prevent renal impairment. There has been debate over the utility of preoperative imaging prior to the harvesting of a fibula flap, but most studies have shown that clinical examination alone is not sufficient to identify vascular anomalies, whether congenital or acquired, in the lower limb [26,35,36]. Even experienced surgeons can be misled by more complex vascular anomalies and can unnecessarily delay the operation and endanger the reconstruction. A preoperative assessment of the lower limb's vascular system could benefit the surgeon both at the planning stage and during surgery, since preoperative interventions far outweigh postoperative salvage from the point of view of patient safety and medical liability.

An individual should always be informed about the possibility of harvesting vein grafts, of abandoning the flap intraoperatively, or of using an alternative flap option intraoperatively. Scapula free flaps are a viable alternative to fibula flaps since they can be harvested in a prone position and have been found to have fewer complications at the donor site [37]. Moreover, the scapular vessels are less susceptible to atherosclerotic changes than the lower limb vessels, making them a more suitable option for elderly patients [38].

Complications and Management of Donor Site Closure

Compartmental syndrome has been reported as the primary cause of ischemia after fibula harvesting [19-21,39-46]. This issue relates to the primary closure of the donor site under tension. When a skin paddle is more than four to six centimeters wide, the donor site should be closed with split thickness skin graft [47]. However, Saleem et al. [48] and Sun et al. [46] report cases in which a donor site was considered to be closed under high tension despite a minimally wide skin paddle. As a result, split thickness skin grafting should always be considered for closing the donor site regardless of the size of the skin paddle [18,49]. Additionally, postoperative vigilance should be maintained to detect early clinical signs of compartment syndrome, which can be masked especially when local anesthetic blocks are used [39]. If there is a suspicion of postoperative compartment syndrome, the wound closure should be opened as soon as possible.

Critical ischemic events in the lower limb following free fibula flap harvests are rarely reported in the literature, however, the complications can be catastrophic. Clinical and radiological pre-operative evaluations are critical to identify vascular anomalies or stenotic vessels, facilitate planning, and reduce vascular ischemic events.

Received date: December 27, 2021

Accepted date: February 21, 2022

Published date: April 25, 2022

The data supporting the findings of this case are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to various restrictions, such as the fact that they contain data that may compromise the privacy of research participants.

The study is in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The authors obtained permission from the participants in the human research prior to publishing their images or photographs.

This research has received no specific grant from any funding agency either in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

There are no conflicts of interest declared by either the authors or the contributors of this article, which is their intellectual property.

It should be noted that the opinions and statements expressed in this article are those of the respective author(s) and are not to be regarded as factual statements. These opinions and statements may not represent the views of their affiliated organizations, the publishing house, the editors, or any other reviewers since these are the sole opinion and statement of the author(s). The publisher does not guarantee or endorse any of the statements that are made by the manufacturer of any product discussed in this article, or any statements that are made by the author(s) in relation to the mentioned product.

© 2022 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY). In accordance with accepted academic practice, anyone may use, distribute, or reproduce this material, so long as the original author(s), the copyright holder(s), and the original publication of this journal are credited, and this publication is cited as the original. To the extent permitted by these terms and conditions of license, this material may not be compiled, distributed, or reproduced in any manner that is inconsistent with those terms and conditions.

Controversies have recently arisen regarding post-operative haemorrhagic complications in relation to the surgical procedures adopted for tonsillectomy. The authors set out to verify the relationship between surgical techniques and post-operative haemorrhage based on the analysis of data derived from multi-centric studies.

Radiation forms a vital part of neoadjuvant treatment in locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) and recurrent rectal cancers. The adverse effects of radiation are well recognized; however, radiation-induced perforation at the tumour site is very rare and is poorly understood. A symptomatic rectal perforation requires an emergency surgical intervention. However, it may present silently and can give rise to suspicion of disease progression and/or residual disease on imaging. Authors present two cases of silent perforations. Both gave rise to a considerable diagnostic dilemma, which was resolved by careful evaluation with MRI.

This study examined two surgical techniques commonly used for turbinate reduction (i.e., submucous resection and partial excision) and their associated complications in functional nasal surgery patients. So far, there has been no direct comparison of these two methods with endpoints of epistaxis and nasal congestion. It was found neither technique was statistically significantly different from the other, so both are clinically useful with a low incidence of postoperative epistaxis.

This article presents a crucial case report on potential wound healing complications linked to fremanezumab, a calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeting antibody for migraine prevention. It documents the first known instance of delayed wound healing following a free flap breast reconstruction, underscoring the need for heightened clinical vigilance and individualized patient assessment in perioperative settings. Highlighting significant safety data gaps, the report advocates for comprehensive research and rigorous post-marketing surveillance. The findings emphasize the importance of balancing the risks of delayed wound healing with the need for effective disease control, especially when using biologic agents for chronic conditions. This article is essential for medical professionals managing patients on biologic therapies, offering critical insights and advocating for a personalized approach to optimize patient outcomes. By presenting novel observations and calling for further investigation, it serves as a vital resource for enhancing patient care and safety standards in the context of biologic treatments and surgical interventions.

This systematic review and meta-analysis provide a pragmatic evaluation of drain-free versus drain-based DIEP flap techniques for breast reconstruction, challenging the traditional reliance on drainage. By analyzing postoperative outcomes, the study highlights the potential for refining surgical strategies to enhance patient comfort and recovery without compromising safety. The findings offer a neutral perspective, suggesting that clinical practice may not necessarily depend on the use of drains. This revelation prompts medical professionals to reassess existing surgical approaches and may catalyze a paradigm shift in postoperative care. Presented with clear narrative and rigorous data analysis, the article encourages readers to consider the broader implications of surgical innovations on patient care protocols.

The senior author (Dr. Isao Koshima) designed a tibial osseo-periosteal (TOP) flap. TOP flap has a favorable anatomical position with a thin skin around it, hence it is a good option for an island flap. TOP flap can be used for various mild to moderately sized osteo-cutaneous defects with low morbidity. In this article, the authors describe their experience of the first reported cohort of TOP flaps in clinical practice.

This case highlights the use of a bipedicled deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap for reconstructing a massive 45 × 17 cm chest wall defect following bilateral mastectomy. By preserving abdominal musculature and utilizing preoperative computed tomographic angiography (CTA) for perforator mapping, the technique enabled tension-free bilateral microvascular anastomosis to the internal mammary arteries. The incorporation of submuscular mesh and minimal donor-site undermining maintained abdominal wall integrity. At six-month follow-up, no hernia or functional deficits were observed, and the patient reported high satisfaction on the BREAST-Q. This muscle-sparing strategy offers a viable alternative for large, midline-crossing chest wall defects where conventional flaps may be insufficient.

This study introduces an advanced tubularized radial artery forearm flap (RAFF) technique, marking an enhancement over traditional methods in addressing complex nasal reconstructions. It integrates functional and aesthetic considerations through a structured, multi-stage reconstruction process, emphasizing the use of tubularized flaps. Key learning points include the detailed crafting of stable nasal passages, strategic use of costal cartilage for robust structural support, and tailored postoperative care with silicone splints. The tubularized RAFF technique not only optimizes patient outcomes and quality of life but also provides plastic surgeons with critical insights to refine their techniques in facial reconstruction. Indispensable for professionals in the field, this article enriches the understanding of sophisticated reconstructive challenges and solutions.

This manuscript showcases an advanced surgical approach for treating malignant giant cell tumor of bone, emphasizing precision and ethical considerations. It leverages innovative pedicled flap technologies, as opposed to free flaps, enhancing limb functionality and patient quality of life. This technique equips surgeons with evidence that tailored surgical strategies can significantly improve outcomes in complex cases. The paper discusses technical challenges and highlights the application of supercharging and superdrainage techniques in limb reconstructions, methods well-established in microsurgery but infrequently used in oncological contexts. These techniques are crucial for optimizing flap viability and ensuring surgical success. Additionally, the manuscript underscores the profound impact of these advancements on patient lives, offering hope and showcasing tangible benefits. This narrative, blending scientific analysis with patient stories, enriches the understanding of limb reconstruction innovations in oncological surgery, making it invaluable for surgeons.

Linderson A, Dimovska EOF, Rodriguez-Lorenzo A. Donor site ischemic events following fibula flap harvest in head and neck reconstruction: A case report and perioperative management strategies. Int Microsurg J 2022;6(1):1. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.imj.2022.00159