Introduction: Oropharyngeal hemorrhage is a rare but life-threatening complication of oropharyngeal tumors. Bleeding episodes such as these can quickly lead to airway obstruction, aspiration and can result in asphyxiation. Nascent otolaryngology residents who have recently graduated medical school are expected to manage this situation with scant amount of prior experience. Simulation offers the unique opportunity to learn procedural skills to a resident/trainee in a safe, controlled environment designed to have specific, obtainable educational goals without any risk to the patient.

Methods: In this study, we created a simulation scenario in which junior otolaryngology residents learned to properly and safely manage a patient with an oropharyngeal bleed while also learning to properly interact and communicate with fellow healthcare providers in a tense, emergent situation.

Results: A 5-point Likert scale survey was utilized to assess realism and benefit from the simulation. An average score of 4.7 points was obtained for this simulation.

Conclusion: We developed an effective and realistic oropharyngeal bleeding mass scenario that was well received by participants in preparing them for real life scenarios.

Oropharyngeal hemorrhage is a rare but life-threatening complication of oropharyngeal tumors [1]. They can occur quickly, and with or without stimulation of the tumor. Bleeding episodes such as these can quickly lead to airway obstruction, aspiration and can result in asphyxiation [1]. Oropharyngeal bleeds are associated with these dangerous outcomes and also have a high mortality rate because safe management of these cases can be rather complex [1]. Nascent otolaryngology residents who have recently graduated medical school are “expected to triage and manage airway [and] bleeding with little prior experience [2].” Further, due to the emergent nature of these bleeds, the approach to rapid patient stabilization likely involves providers from different specialties working side by side to manage this life-threatening condition. This can make for a stressful setting in which conflicting medical opinions pertaining to management may arise. With all of this in mind, we created a simulation scenario in which our junior residents learned to properly and safely manage a patient with an oropharyngeal bleed while also learning to properly interact and communicate with fellow healthcare providers in a tense, emergent situation. The goals of the study were to apply airway management and leadership skills in the context of a clinical team as well as to identify and adapt to clinical changes in real time.

This scenario was designed for the training of first year residents (interns), however it can be used for residents at any level of training. In order to benefit most from this scenario, the participating intern/resident should have a background of the basic anatomy of the oropharynx prior to running through the simulation. Table 1 shows a list of equipment needed for both the mannequin setup and for the oropharyngeal bleed simulation.

Mannequin Setup

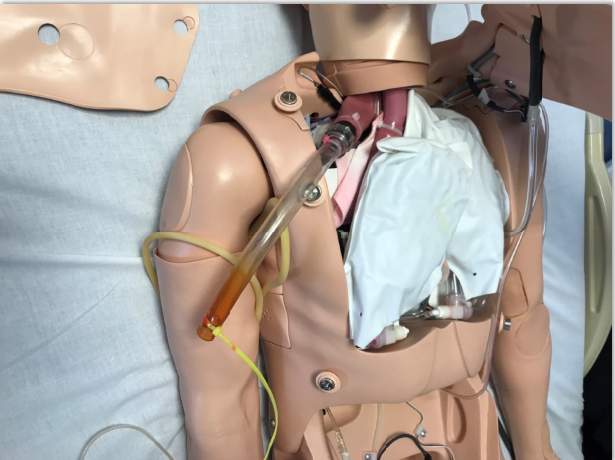

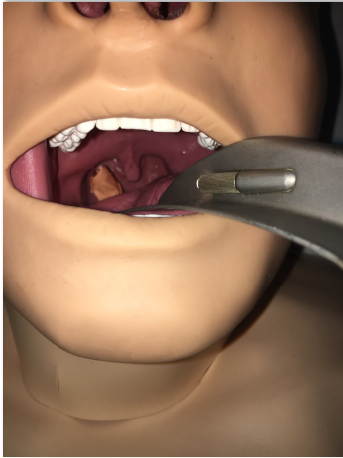

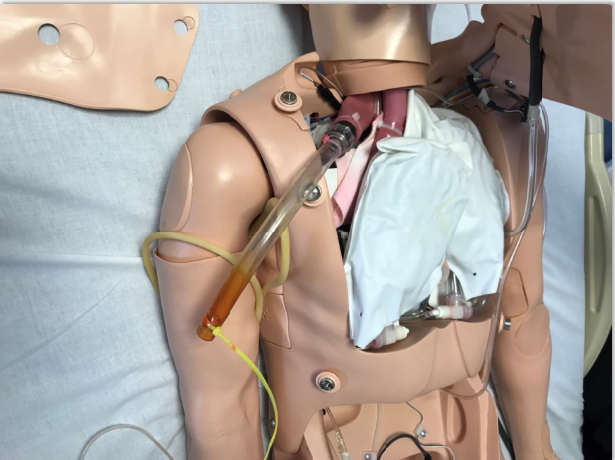

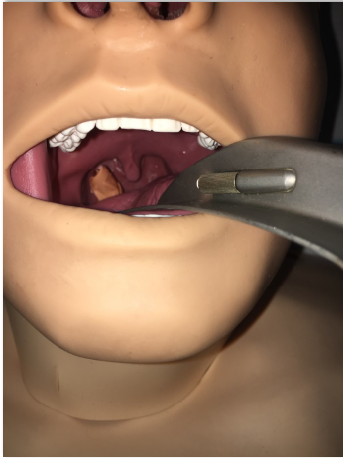

Our oropharyngeal tumor simulator was created to train our otolaryngology junior residents on management of oropharyngeal bleeding. Realism is enhanced through the specific, novel, selection of the manikin for modification. We used the electronic simulator Laerdal ALS Mannequin. The mannequin breathes, has lung sounds, heart sounds, talks and has the capacity to display vital signs. To set up for this simulation, the abdominal bag was removed and padded with absorbent disposable fluff underpads (chucks) to absorb any residual fluids that ran along the pharynx into the mannequin (Figure 1). The chest skin was also removed, and the internal mechanics were covered with a towel and chucks (absorbable side up) to capture any residual fluids. We then disconnected the esophagus from the mannequin’s abdomen (Figure 2) and placed the bottom of the esophagus into a plastic bag to prevent fluid from damaging the innards of the mannequin. IV tubing, attached to a pre-mixed 3L bag of artificial blood, and extension tubing, was then threaded through the esophagus into the oropharynx (Figure 3). The cuff of a 6.5 ET tube was inflated, and the ET tube tip was cut off. A portion of the proximal end of the ETT tube was also removed with a scissor. The inflated balloon was then covered with HY-Tape® to make the mass look more realistic (Figure 4). The IV tubing from the oropharynx (that was threaded up the esophagus) was then pulled up using Magill forceps and threaded through the inverted ET tube (Figure 5), letting the opening of IV tubing to sit right at the inflated balloon of the ET tube. The inverted tube, with the IV tubing still inside was then placed into the oropharynx using Magill forceps, allowing the balloon to sit in the oropharynx (Figure 6), and the superior part of the tube to go down the pharynx.

Figure 1. Preparation of the mannequin for simulation step 1.

Figure 2. Preparation of the mannequin for simulation step 2.

Figure 3. Intravenous tube placement.

Figure 4. Construction of the oropharyngeal mass.

Figure 5. Preparation of the oropharyngeal mass for bleeding.

Figure 6. Placement of the oropharyngeal mass.

Bleeding

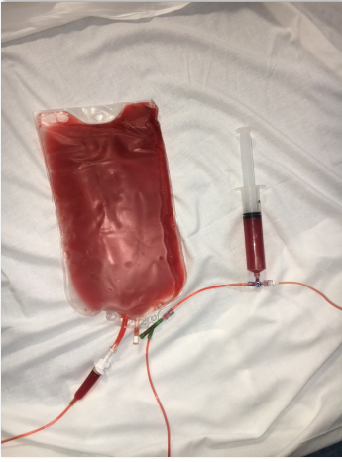

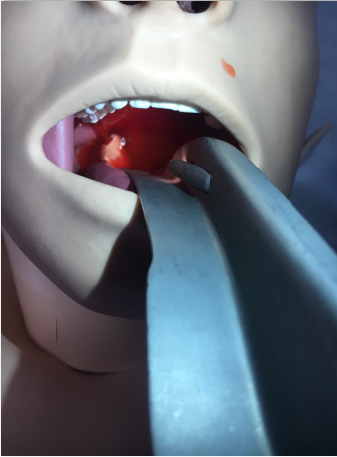

In order to facilitate bleeding (Figure 7), we used two different, but equally effective techniques.

Version 1

An Alaris 8015 pump tubing is connected to the extension tubing with a 3L bag of pre-mixed artificial blood. To express minimal continual bloodflow, the pump was set to express 500 ml in 10 minutes. Greater blood flow is achieved by increasing the rate of the pump. Up to 1 liter of blood should be aimed to be expressed per learner. The pump is positioned behind the mannequin. This version requires manual changes of pump setting to increase blood flow.

Version 2

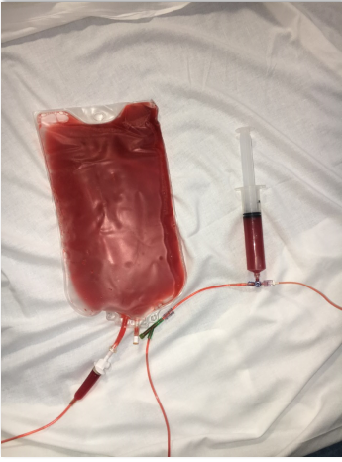

To express greater blood volume and force associated with emergent bleeding cases, a manual hand pump is utilized. A three-way stop-cock is attached to the extension IV tubing. A 60 CC syringe is connected to one port. The remaining port is attached to a pre-mixed 3L bag of blood via an Administrator Extension set and IV tubing (Figure 8). The Simulation Technician is positioned behind the bed, out of the learner’s line of sight. Using the 60 CC syringe and three way stop cock, blood is drawn up into the syringe from the 3-liter reservoir bag. After the syringe is completely full, the stopcock is then switched to allow blood to be expressed from the syringe into the patient’s oropharynx. Blood is then expressed from the syringe, at the desired rate, to cause oropharyngeal bleeding. The process is repeated continuously throughout the scenario. After the mannequin setup is complete, the learner can then manage the oropharyngeal bleeding as directed by the instructor/scenario.

Figure 7. Bleeding from the oropharyngeal mass.

Figure 8. Bleeding equipment setup: version 2.

Scenario

The intern/learner is paged to the intensive care unit (ICU) for a 69-year-old male with history of oropharyngeal cancer complaining of oral bleeding. The ICU attending is at the bedside. Table 2 shows the vital sign setting.

The intern/learner assesses the patient who complains of difficulty breathing as he/she is coughing up blood. The ICU attending urges the intern/learner to help the patient. The intern/learner should first attempt to suction the airway and use a fiber optic scope to establish the source of the bleed. If scoped correctly, the source of the bleed should be identified as the bleeding mass in the posterior oropharynx. As more time passes, the patient’s oxygen saturation continues to drop, and he becomes increasingly tachycardic. Seeing the dropping oxygen saturation, the ICU attending questions the intern/learner if an orotracheal intubation could be a good treatment option for this patient. The intern/learner should explain to the ICU attending the risks associated with sedating a patient with an oropharyngeal mass. As the patient’s oxygen saturation continues to drop, the intern/learner should assess the feasibility and safety for an attempted nasotracheal intubation. If the intern/learner deems a nasotracheal intubation safe, he/she should attempt to perform one. If successfully placed, the patient’s oxygen saturation should increase, and vitals should stabilize.

If the intern/learner is not able to perform a nasotracheal intubation, or if the patient destabilizes at any point in the scenario, the intern/leaner should perform a cricothyroidotomy. If the intern/learner is unsuccessful in managing the scenario, the patient will continue to decompensate. If at any point, the intern/learner sedates the patient, the patient should decompensate. At the conclusion of the scenario, participants were then asked to fill out a 5-point Likert score to assess realism and perceived benefit from the simulation.

To ensure benefit from this scenario, a pre-training and post-training assessment can be used as well.

Over the last 2 years, 8 interns completed this simulation. A 5-point Likert scale survey was utilized to assess resident perceived realism and benefit from this simulation. An average score of 4.7 points was obtained for this simulation.

The expeditious transition from a senior medical student to a junior resident can be a daunting, and overwhelming experience. Coming from a sheltered and protected environment to one that is fraught with patient encounters, situation- based decisions and technical skills can cause much stress for a new intern [3]. In addition to the stress put on the resident, evidence has emerged that there is more incidence of physician error causing patient harm in the beginning of residency [4]. This situation can be made even worse when entering a surgical and a procedure-laden subspecialty such as otolaryngology, where the technical skills are so specialized that some of them are not taught in medical school [5]. To mitigate this issue, attempts have been made, through simulation and boot camp training, to equip these novice residents with the skills needed to succeed in their new role.

Simulation offers the opportunity to learn procedural and interviewing skills to a resident/trainee in a safe, controlled environment that is designed to have specific educational opportunities without serious risk to the patient [3,6-11]. Just as it applies to the military, boot camp style learning emphasizes teaching novices the basic skills necessary to properly function in a real-world scenario. In otolaryngology, the ultimate goal is to transition “undifferentiated senior medical students to dedicated otolaryngology residents [3].” With the advent of duty hour restrictions and resource limitations, training a resident in a shorter period of time and in a more modifiable environment is being more heavily favored than traditional teaching of only experiencing a medical emergency in a real-life situation [2,3,7,12,13]. By putting these skills into a boot camp style course, residents are given the opportunity to participate in intense-style training while still being taught in a safe, simulated environment.

Time and time again, simulation-based training has shown its effectiveness in the medical field, and specifically in the field of otolaryngology [14-16]. A study in 2015 by Chin et al. found that “an otolaryngology boot camp gives residents the chance to learn and practice emergency skills before encountering the emergencies in everyday practice. Their confidence in multiple skill sets was significantly improved after the boot camp [7].” Other studies have also shown similar results in medicine and the field of otolaryngology [17,18]. All of these studies have consistently shown that through simulation and boot camp training, residents began developing the appropriate knowledge, skill set and self-confidence [2,7] needed to succeed during residency and, more importantly, that these skills transferred to real clinical situations/procedures with real patients.

Due to the proven success of simulation-based learning, we have created a scenario in which our residents can practice how to properly manage an oropharyngeal bleed. Vascular erosion, causing a hemorrhagic episode, can occur in all patients with advanced-stage tumors, recurrent tumors, infection and pharyngocutaneous fistulas [1,19]. Additionally, when chemotherapy and radiation are used in conjunction, without surgical intervention, secondary adverse effects can arise, including “erosion of skin and mucosa…. premature atherosclerosis with stenosis and weakening of arterial walls due to adventitial fibrosis, fragmentation of elastic filaments, and destruction of vasa vasorum. Following chemoradiation, therapy, spontaneous hemorrhage can result as a consequence of weakened arterial walls [1].” This complication, especially in tumors arising from the oropharynx can be particularly devastating.

These emergent situations must be recognized and cared for quickly to prevent blood loss, aspiration and/or asphyxiation. However, caution must be used when managing a patient like this, as a wrong step can put the patient at serious risk. A patient with a bleeding oropharyngeal mass who loses consciousness or is anesthetized, may lose the ability to protect his/her own airway and the bleeding may continue to flow distally, causing asphyxiation [20]. Further, endotracheal intubation can irritate and stimulate the bleeding lesion, thus exacerbating the bleeding and making airway management even more difficult [20]. With these complications in mind, nasotracheal intubation is seen as the safest and most effective way of securing an airway in these patients. Our simulation allows our residents to systematically work through the critical decision-making process in a safe environment, in order to acquire the knowledge as well as the manual dexterity to properly manage these patients.

As with other medical emergencies, managing an oropharyngeal bleed can be stressful. Working with healthcare providers of a different specialty can sometimes add to the stress, as there may be differing opinions related to patient management. Junior residents can be more susceptible to these stressors, as they may lack the experience and confidence needed to make a decision in the face of conflict. While the leader of the medical team is ultimately in charge of the decision-making during a medical emergency, there may be times when a trainee from one specialty may not agree with a treatment decision made by an attending of a different specialty. In this situation, we want to foster professionalism, collaboration, leadership and communication skills between both medical providers from different training backgrounds. In a study performed by Belyansky et al., it was found that “74-78% of trainees and attendings recalled an incident where the trainee spoke up and prevented an adverse event. While all attendings in this study reported that they encourage residents to question their intraoperative decision making, only 55% of residents agreed [21].” By being encouraged to voice concerns during an emergency, trainees can act as partners in the reduction of possible medical errors. Further, in a literature review by Ignacio et al., it was found that “excessive stress and/or anxiety in the clinical setting have been shown to affect performance and could compromise patient outcomes [22].” In and out of the field of medicine, studies have “suggested that stress training showed an improving trend in performance…. [and was a] valuable strategy for enhancing… thought process and improving… performance in communication skills [22].” By presenting the junior residents with a stressful situation in which an attending suggests a management option that might not be appropriate for the patient, the residents learn how to properly and respectfully suggest an alternate treatment approach, while also learning the technical skills needed to properly care for such a patient. This provides the resident with the tools necessary to deal with such a situation, when it is appropriate, during residency and beyond. Using this simulation, the learner is encouraged to move from comprehension and application to synthesis and evaluation.

The novelty of this scenario comes from both the setup of the mannequin, and the use of the mannequin with the designed scenario. By using this simulation, the intern/learner learns how to both utilize the treatment algorithm for a bleeding oropharyngeal mass and work with members of medical teams composed of members from different specialties and experience levels. This simulation facilitates the development of technical, knowledge-based and interpersonal skills all within a succinct and collaborative educational environment.

Using a safe and controlled simulation environment, we were able to develop an effective and realistic oropharyngeal bleeding mass scenario that was well received by participants.

Received date: May 09, 2018

Accepted date: June 29, 2018

Published date: July 13, 2018

None

None

© 2018 The Author (s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).

The authors have addressed comments and concerns about a recent article, by Nasr et al, which reported the clinical characteristics and outcome of 34 patients with Takotsubo syndrome triggered by cerebral disease and collected during five years from a neurological ICU.

Epistaxis (i.e., nosebleed) is a common otolaryngologic emergency; however, it is seldom life-threatening and most minor nosebleeds stop on their own or under primary care from medical staff. Nonetheless, cases of recurrent epistaxis should be checked by an otolaryngologist, and severe nosebleeds should be referred to the emergency department to avoid adverse consequences, including hypovolemic shock or death. This paper reviews current advances in our understanding of epistaxis as well as updated treatment algorithms to assist clinicians in optimizing outcomes.

The authors report the first published case of a patient presenting with stridor from an acute, near complete, airway obstruction with normal biochemical markers, as the initial presentation of a parathyroid adenoma, which required immediate surgical intervention. The learning point from this case is to ensure a broad differential is placed forward when dealing with acute neck swelling. Routine Head and Neck pathology can present in an unusual fashion, with resultant challenging presentations.

Dysphagia is an important consequence of cancer treatment and has overarching implications on quality of life. Using the FOIS, we demonstrated that swallowing function may be worse in the long term in patients with OPSCC undergoing triple therapy, although this finding did not reach statistical significance. This study emphasizes the importance of diligent selection in patients undergoing TORS to avoid poor functional swallowing outcomes, particularly in those that may need adjuvant chemoradiation therapy. A study with a larger sample size may determine the significance of these trends.

Establishing a relationship between a benign disorder and a malignant disease has a certain influence on clinical practice. Clinicians need to remain vigilant with patients with acid reflux disorders and rule out the possibility and presence of head and neck cancer.

The review article presents an expansive list of otolaryngology-specific surgical simulation training models as described in Otolaryngology literature as well as evaluates recent advances in simulation training in Otolaryngology.

The review article presents an expansive list of otolaryngology-specific surgical simulation training models as described in Otolaryngology literature as well as evaluates recent advances in simulation training in Otolaryngology.

In a cost-effective and portable way, a novel method was developed to assist trainees in spinal surgery to gain and develop microsurgery skills, which will increase self-confidence. Residents at a spine surgery center were assessed before and after training on the effectiveness of a simulation training model. The participants who used the training model completed the exercise in less than 22 minutes, but none could do it in less than 30 minutes previously. The research team created a comprehensive model to train junior surgeons advanced spine microsurgery skills. The article contains valuable information for readers.

The authors present a novel synthetic vascular model for microanastomosis training. This model is suitable for trainees with intermediate level of microsurgical skills, and useful as a bridging model between simple suturing exercise and in vivo rat vessel anastomosis during pre-clinical training.

The review article presents an expansive list of otolaryngology-specific surgical simulation training models as described in Otolaryngology literature as well as evaluates recent advances in simulation training in Otolaryngology.

Authors discuss a silicone tube that provides structural support to vessels throughout the entire precarious suturing process. This modification of the conventional microvascular anastomosis technique may facilitate initial skill acquisition using the rat model.

PEDs can be used as alternative means of magnification in microsurgery training considering that they are superior to surgical loupes in magnification, FOV and WD ranges, allowing greater operational versatility in microsurgical maneuvers, its behavior being closer to that of surgical microscopes in some optical characteristics. These devices have a lower cost than microscopes and some brands of surgical loupes, greater accessibility in the market and innovation plasticity through technological and physical applications and accessories with respect to classical magnification devices. Although PEDs own advanced technological features such as high-quality cameras and electronic loupes applications to improve the visualizations, it is important to continue the development of better technological applications and accessories for microsurgical practice, and additionally, it is important to produce evidence of its application at surgery room.

In a cost-effective and portable way, a novel method was developed to assist trainees in spinal surgery to gain and develop microsurgery skills, which will increase self-confidence. Residents at a spine surgery center were assessed before and after training on the effectiveness of a simulation training model. The participants who used the training model completed the exercise in less than 22 minutes, but none could do it in less than 30 minutes previously. The research team created a comprehensive model to train junior surgeons advanced spine microsurgery skills. The article contains valuable information for readers.

An examination of plastic surgery residents' experiences with microsurgery in Latin American countries was conducted in a cross-sectional study with 129 microsurgeons. The project also identifies ways to increase the number of trained microsurgeons in the region. The authors claim that there are few resident plastic surgeons in Latin America who are capable of attaining the level of experience necessary to function as independent microsurgeons. It is believed that international microsurgical fellowships would be an effective strategy for improving the situation.

The revised manuscript is accepted for publication.

I accept this article.

The paper can be accepted for publication.

Feintuch J, Feintuch J, Kaplan E, Hollingsworth M, Yang C, Gibber MJ. Novel otolaryngology simulation for the management of emergent oropharyngeal hemorrhage. Arch Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;2(1):3. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.aohns.2018.00068