Background: The versatility of pedicled latissimus dorsi (LD) flap is well known for the reconstruction of the breast, upper limb, and trunk defects. Extensive soft tissue defects following oncologic resections around the clavicle are rare and the utility of pedicled LD muscle flap has been less reported.

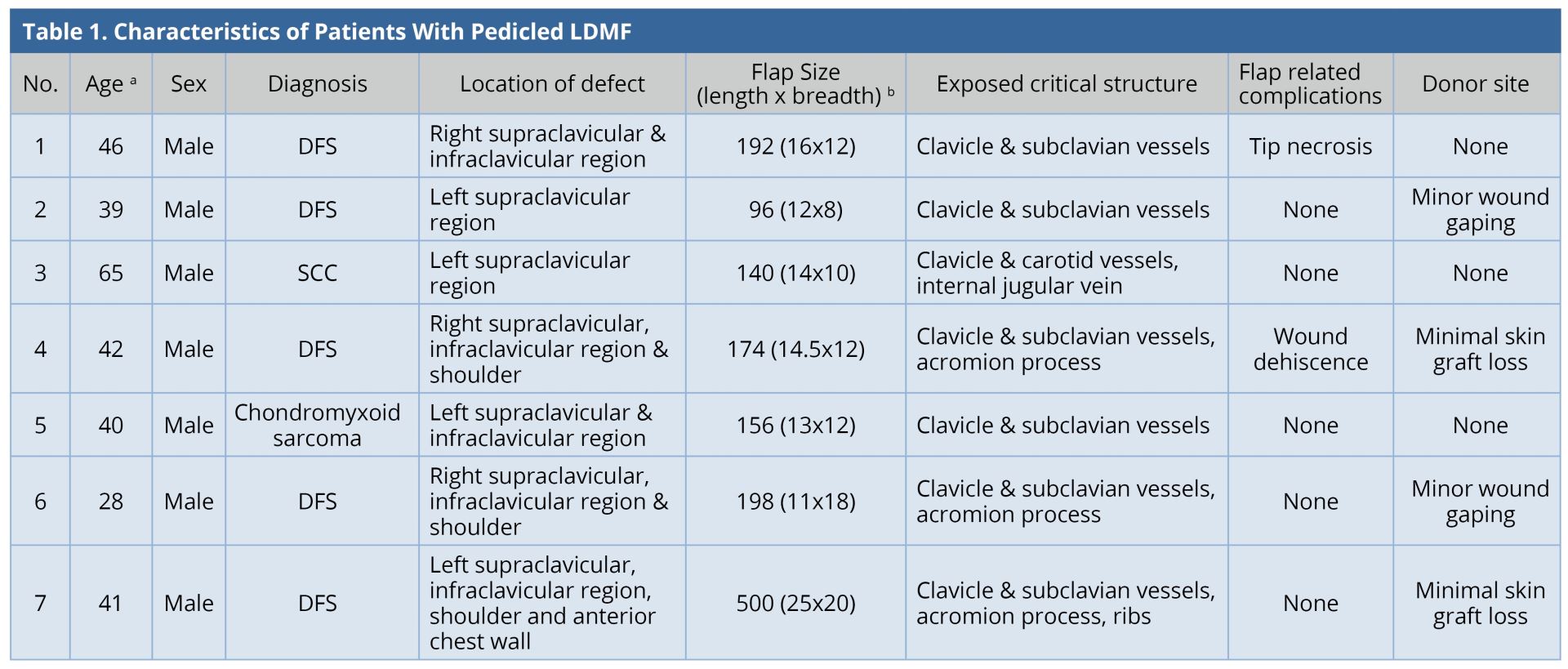

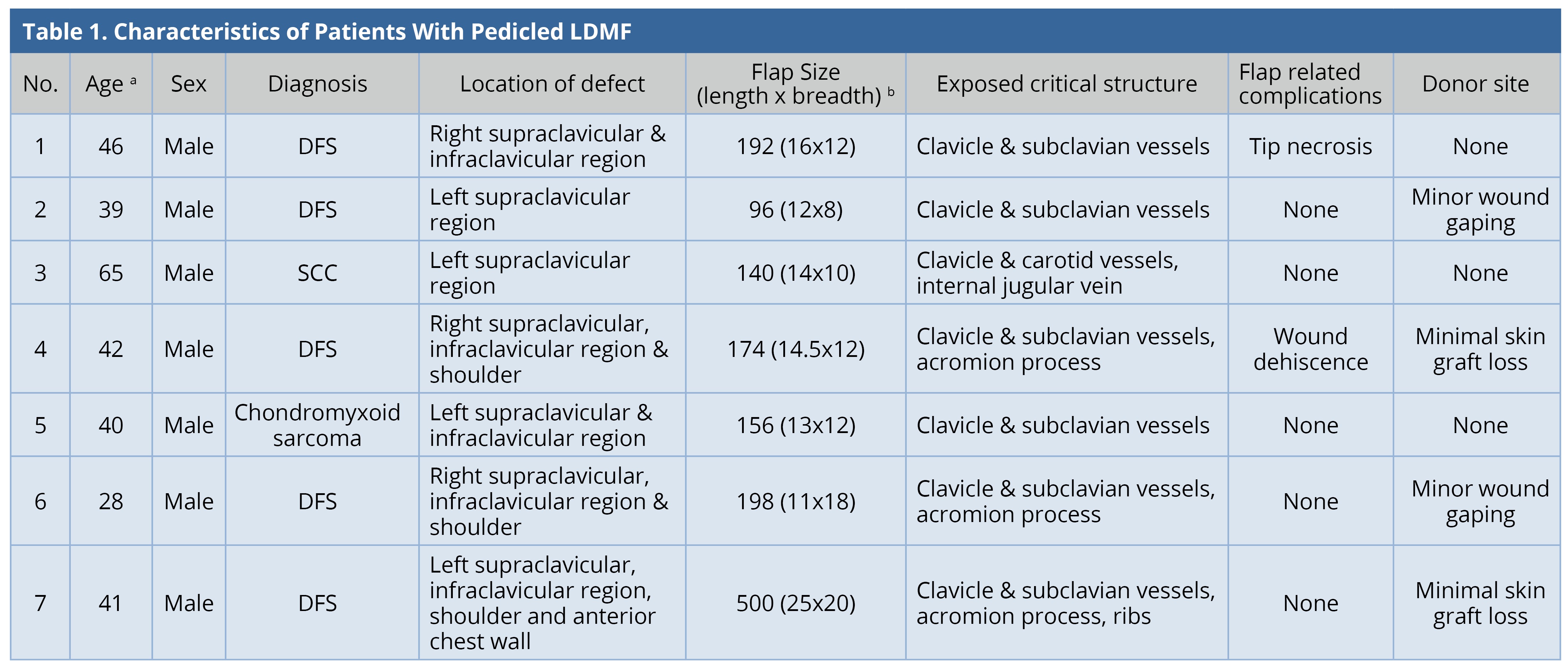

Methods: Retrospective review of 7 patients who underwent wide excision of the malignant tumors around the clavicle was done between January 2016 and June 2018. Patient demographics, clinical details, the arc of rotation, outcome, and complications were analyzed.

Results: All flaps were successful with minor flap-related or donor site complications observed in 5 patients. These minor complications resolved with local care.

Conclusion: Pedicled latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap is an ideal choice and a good alternative option to free flap for reconstruction of the oncological soft tissue defects around the clavicle. Minor donor site complications can occur if the donor site is covered with skin grafting.

Wide excision of the soft tissue tumors around the clavicle results in extensive defects frequently leading to exposure of critical neurovascular and skeletal structures. Early healing and stable vascularized soft tissue coverage are necessary for adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy in many instances. When the lesions extend to the shoulder region, flap coverage is recommended to prevent wound contraction and restriction of shoulder movements. Very few local/regional options are available for coverage of these extensive soft tissue defects. Free tissue transfer is an alternative option to pedicle flaps. However, there is an increased requirement of operating time, resources, and the risk of total flap loss. The latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap (LDMF) is a versatile option to cover these defects due to its large vascularized surface area, long vascular pedicle, and less donor site morbidity. The aim of this study is to share our technique and analyze the outcomes in this case series.

Retrospective analysis of seven patients who underwent wide excision of the malignant tumors around the clavicle was done between January 2016 and June 2018. Patient demographics, clinical details, the arc of rotation, outcome, and complications were analyzed.

Surgical Techniques

Latissimus dorsi muscle was evaluated by palpating the muscle at the posterior axillary fold while resisting the shoulder adduction during the preoperative workup. Once the malignant lesion was excised and the defect was created by the general surgeon, we took over the patient. The patient was turned into the lateral decubitus position and the latissimus dorsi muscle boundaries were marked. The anterior border of the muscle was marked along the posterior axillary line and the upper border was marked at the tip of the scapula, medially at the spinous process of the vertebra and inferiorly at the posterior aspect of the iliac crest. The skin paddle was designed over the muscle, predominantly over the upper two-thirds of the muscle, to include the high density of myocutaneous perforators. The length and breadth of the defect were noted and one end (distal) of the surgical mop was cut according to the dimensions of the defect and placed over the defect. The other end (proximal) of the mop was located at the apex of the axilla. According to the principles of planning in reverse, the proximal end of the mop was fixed at the axilla and the distal end was rotated in a clock wise fashion to reach the back (latissimus dorsi muscle territory). This simulated the arc of rotation of the flap after the harvest. The distal end of the mop was placed over the latissimus dorsi (LD) territory and the skin paddle was marked. The incision was made to identify the lateral border of the LD muscle; the lateral border was retracted and the muscle was separated from the serratus anterior by blunt dissection. The skin flaps were further dissected avoiding shearing between the muscle and the skin paddle of LDMF. The superior edge was dissected from the scapular tip. The muscle was divided inferiorly and medially as per the flap dimensions. The thoracodorsal pedicle was identified tracing the vessels of serratus anterior, and the latter was divided to allow rotation of the LDMF across the axilla. To improve the reach of the flap, the insertion of LD muscle was transected in 2 patients. The thoracodorsal vessels were dissected towards their origin to prevent kink during the rotation of the flap to cover the defect. Thoracodorsal vessels act as the pivot point. A subcutaneous tunnel was made to deliver the flap into the defect in most of the cases. In our entire cases, the flap was rotated anticlockwise with the subcutaneous tunnel located in the anterior aspect. The tunnel was kept adequately broad to prevent flap compression. After tunneling, the flap vessel kink should be ruled out. Split-thickness skin grafting was performed at the donor site and a tie overdressing was done in 6 of 7 patients (Figure 1 and 2). Flap inset was made after placement of drains. Postoperatively, the shoulder was immobilized at 45-degree abduction and gentle physiotherapy was started from the 5th postoperative day.

Figure 1. (A) Large ulcerated dermatofibrosarcoma over the right clavicular lesion. (B) Ipsilateral LDMF after complete dissection. (C) Demonstrating anticlockwise rotation of the flap before tunneling to reach the defect. (D) Before inset. (E) Well-settled flap. (F) Healed donor site wound.

Figure 2. (A) Recurrent left dermatofibrosarcoma over the left clavicle (skin graft of previous surgery is seen). (B) Exposed clavicle and subclavian vessels after wide excision of the lesion. (C) Harvested ipsilateral pedicled LDMF. (D) Flap reach before tunneling. (E) Well settled flap. (F) Healed donor site wound.

All the flaps survived. The mean surface area of the flap was 208 cm2 (range: 96-500 cm2). Two patients (28.5%) had minor flap-related complications. One of them had tip necrosis at the distal-most portion of the flap, which was managed by minor debridement and the wound healed by local wound care. The other patient had minor flap dehiscence, which was sutured under local anesthesia. All except one patient required skin grafting at the donor site. Four patients (57%) had minor donor site complications. Two patients had minimal graft loss; two patients had wound dehiscence; all were healed by local wound care. The results were tabulated (Table 1). Two patients underwent adjuvant radiotherapy and one underwent chemo-radiotherapy. The mean follow-up duration was 1.5 years. Two patients were lost to follow-up. There was no recurrence in any of the patients under follow-up. All patients were satisfied with the functional result.

a Age in years.

b Flap Size in cm2.

DFS, Dermatofibrosarcoma; LDMF, latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap; SCC, Squamous cell carcinoma.

Multimodality approach, including surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy is required for complete eradication of malignant tumors. Frequently, wide excision of the soft tissue tumors precludes primary skin closure. If the wound bed is appropriate, skin grafting following sarcoma excision is well established [1]. Skin graft reaction to radiotherapy is similar to normal skin after 3-4 weeks of application [2]. When a critical structure is exposed, and the wound bed is unfit for a skin graft, the flap coverage is essential. There are insufficient local/regional flap options for coverage of extensive soft tissue defects around the clavicle. Though LDMF is a versatile option in straightforward cases, it is to be avoided in cases of prior radiotherapy or axillary lymph node dissection [3]. Pectoralis major is an alternative option. It is closer to the clavicular defects and provides both muscle and skin paddle. Pectoralis major flap would be the first choice for smaller defects, which would facilitate donor site closure. For larger soft tissue defects, the resultant donor site would require a skin graft. This resultant donor site deformity is more conspicuous in the anterior chest wall. We preferred LDMF over pectoralis major flap as we encountered very large soft tissue defects, which required a bulky flap to fill the three-dimensional defect. The LDMF provides large muscle, which can be folded to obliterate the cavities around the clavicle. Moreover, the thoracoacromial pedicle was sacrificed in most of the cases and hence the option of pectoralis major flap was excluded in our series. The pedicle of LDMF is longer as compared to the pectoralis major flap, which facilitates easy positioning. Pectoralis minor [4] has also been described for coverage of smaller defects around the clavicle. Trapezius myocutaneous flap is also an option, but it is limited by the size of the flap and significant donor site morbidity [5]. LDMF is the ideal flap for these defects as it is easy to master, less time taking, high success rate, and avoids complex microvascular surgery.

Free flaps have a definitive role if thoracodorsal vessels are damaged in prior surgery or radiotherapy. They are also useful in the reconstruction of the composite defects where simultaneous clavicle and soft tissue cover are reconstructed [6]. None of our patients underwent resection of clavicle as the tumor was not infiltrating it. The periosteum was stripped and sent for pathological examination. None of them had infiltration of periosteum. However, the patients underwent adjuvant radiotherapy if the lesion was abutting the clavicle. If clavicle was resected, we would prefer a vascularized fibula flap for the reconstruction. LD flap can be used either as a muscle or as a myocutaneous flap for coverage of wounds around the clavicle. Al-Qattan NM et al. [7] used LD muscle flap and skin grafting, thereby closing the donor site primarily. This procedure has the advantage of avoiding the donor site morbidity due to skin grafting in the back. It is critical to know regarding the optimal time for giving adjuvant radiotherapy. It has been proven experimentally and clinically that minimum 3 weeks interval is required after successful coverage of the wound with a skin graft [1]. In the event of partial skin graft loss, it is recommended to wait until the wound is completely healed before radiotherapy.

On the contrary, numerous surgeons prefer flaps over skin grafts if adjuvant radiotherapy is required [8]. We preferred myocutaneous flap to avoid the possibility of the unstable wound following radiotherapy over skin grafted wound [9]. Hyperpigmentation, contractures, partial graft loss, and ulceration have been reported following adjuvant radiotherapy to skin grafted wounds [1]. Tadjalli et al. [10] reported graft loss with a radiation dose of > 25G even after complete wound healing within 4 weeks. Adjuvant radiotherapy after 8 weeks of skin grafting improved the results [8]. Myocutaneous flap is bulkier than the muscle flap. It fits into the cavities and gives a uniform appearance. The color match is better with the skin paddle rather than a graft. The skin graft over the muscle flap gets pigmented and gives a hollow appearance in the due course. The latter result is not preferred in our patients as the day-to-day clothing exposes clavicular area rather than the lower back area.

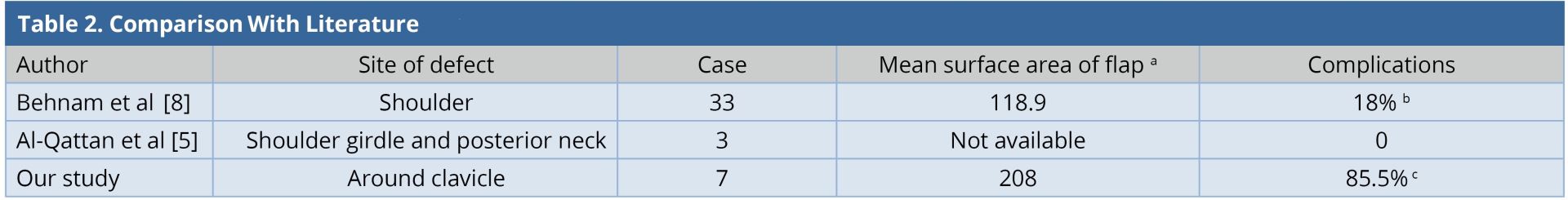

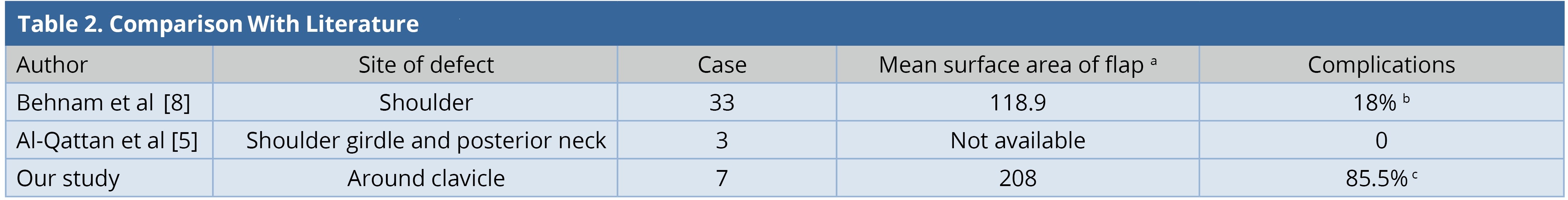

Ipsilateral pedicled LDMF could be used for simultaneous soft tissue coverage and reconstruction of the shoulder abduction when extensive resection of deltoid was performed. The LDMF was harvested in a conventional fashion and islanded after passing through the subcutaneous tunnel; the origin was attached to the clavicle and the insertion to the deltoid tubercle in a bipolar fashion [3]. None of our patients had an extensive resection of the deltoid muscle. In our entire cases, the flap was rotated in anticlockwise direction with a subcutaneous tunnel in the anterolateral aspect of the chest wall. However, when the defect is more posterior and superior to the shoulder, the posterior clockwise rotation of the flap can be done [11]. Large surface area of the flaps in our series led to the requirement of donor site skin grafting. Two patients had minor skin graft loss and two others had minor wound gaping. All of them healed within two weeks by local wound care. One patient underwent axillary dissection and two patients underwent neck dissection. None of them presented to us with brachial plexus neuritis, lymphedema, or clavicle osteoradionecrosis in the follow-up period. Our study is compared with other similar studies (Table 2). The complication (flap-related and donor site) rate in our series was 85%, which was higher than that of the other series [5,8]. This was because of the requirement of larger flaps and thereby, skin grafting at the donor site as compared to other series where donor sites were closed primarily.

a Mean surface area of flap in cm2

b Flap related complications.

c Flap related complications and minor donor site complications.

Pedicled LDMF is an ideal choice and a good alternative option to free flap for reconstruction of the oncological soft tissue defects around the clavicle. Minor donor site complications can occur if the donor site is covered with skin grafting.

Received date: July 19, 2018

Accepted date: August 27, 2018

Published date: February 16, 2019

None

None

© 2019 The Author (s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).

In Table 2, the complication rate in the study is much higher than those of other studies. It would be better if the authors could explain the possible reasons for the difference?

ResponseThe complication (flap related and donor site) rate in our series was 85% which is higher than that of the other series [5,8]. This is because of the requirement of larger flaps and thereby, skin grafting at the donor site when compared to other series where donor sites were closed primarily.

The revised manuscript is accepted for publication.

Accepted for publication.

The authors have addressed all of my concerns. The article is accepted for publication as Case Series.

Naalla R, Raju PK, Sharma MK, Bhattacharya S, Jha MK. Technique and outcomes of pedicled latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap for oncologic defects around the clavicle. Int Microsurg J 2019;3(1):2. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.imj.2019.00098